In the past five years virtually all local trial courts have opened new ADR 1 programs or greatly expanded existing programs so that almost every civil case now being filed will be encouraged or required to go through some form of ADR procedure. 2 In federal court, many cases are automatically ordered into the ADR Multi-Option program at filing and others can be referred by a judge. See U.S.D.C. ADR Local Rule 3-3; see also Rule 2-3 (parties can seek relief from automatic assignment). As a practical matter, even where there is no automatic assignment, judges typically raise the issue at the first case management conference and may refer cases to a court-connected ADR process, usually early neutral evaluation.

The courts are running these programs themselves or are cooperating with the local bar associations who actively manage them. In either case, attorneys trying intelligently to manage litigation are faced with another layer of decisionmaking as they must choose how ADR can best be used to their client’s advantage.

Courts purposefully require litigators to consider, and discuss with their clients, ADR options very early in a case. Superior court cases often are assigned to ADR programs at the first status conference. Some federal court cases are assigned to the Multi-Option ADR program at filing and the parties must choose a particular procedure shortly thereafter; other cases are assigned to a specific ADR procedure at filing or at the first case management conference.

Accordingly, responsible attorneys must plan how to use ADR from the outset. It is difficult for any litigator not handling multiple cases in the same jurisdiction to keep up with the changes in that court, let alone in other local courts. This article summarizes the programs in the Bay Areas superior courts and in federal district court so that attorneys will understand the court-sponsored ADR options available for a particular case when they plan the early stages of the litigation.

Summary of ADR Processes

Local court programs usually include a variety of ADR processes, although not necessarily the same ones. All provide some form of mediation, but some mix mediation with neutral evaluation and others separate the two approaches. This article cannot delineate all the subtle differences in how these programs operate, in part because the way a particular procedure is done will likely vary more with the individual service provider than with the program. It is nonetheless useful to establish what certain terms mean.

In mediation, a neutral person assists the parties to negotiate a settlement by guiding the exchange of information about the dispute and about what the parties wish to accomplish in a settlement, and by offering suggestions on ways of approaching resolution. Mediation in its pure form does not involve the pressure or evaluative content of a traditional judge-directed settlement conference, but in practice mediators vary a great deal in style. Indeed, the pilot San Mateo program asks mediators to characterize their working style as either “Facilitative/Nondirective” (does not make substantive but may make process suggestions) or “Evaluative/Directive” (more akin to a settlement judge).

Neutral evaluation provides the parties with an experienced neutral third party’s opinion about the likely result of the case and its strengths and weaknesses. In practice, this may lead to settlement discussions. In the federal court program, where it is the most popular ADR option, the evaluator reads written submissions, listens to oral presentations, and questions the parties before preparing an evaluation; no ex parte discussions are permitted before the evaluation is completed. But immediately thereafter, the evaluator asks the parties whether they wish to discuss settlement before hearing the evaluation. Many times they do; if so, the procedure becomes more akin to a traditional mediation or settlement conference with private caucuses and shuttle diplomacy. Cases often settle without the parties ever hearing the evaluation.

Both the San Francisco and Contra Costa programs include a hybrid procedure taking on aspects of both early neutral evaluation and mediation. The Early Settlement Program ( ESP ) in San Francisco provides a panel of two litigators or practicing mediators experienced in the subject area who volunteer a day to hear three cases, allotting approximately two hours to each. The neutrals, one with a plaintiff’s perspective and one with a defendant’s, provide some evaluation and explore the possibility of settlement. Having two litigators involved can be a plus, but they can also work at cross purposes when settlement discussions become active. Despite the name, in the typical case the ESP conference occurs two to three months before trial.

Although described in the local rules as an early neutral evaluation project, the Extra Assistance to Settle Early (EASE) program in Contra Costa often operates more like mediation in practice. A single mediator/evaluator is assigned a case and often schedules an entire day, allowing for the possibility of more extended discussions, although only two hours are required under the program rules.

Judicial arbitration is available in all counties, even if it is not managed under the ADR program. Where the ADR program also offers nonjudicial arbitration, the parties can choose whether it is binding or nonbinding. In either case, counsel should be sure they understand what the effect of any decision will be: whether and how it will be enforceable, and what procedure applies after such an arbitration. Often there are no rules explicitly setting out the answers to these questions and attorneys need to discuss this with the program directors and with opposing counsel to avoid disputes.

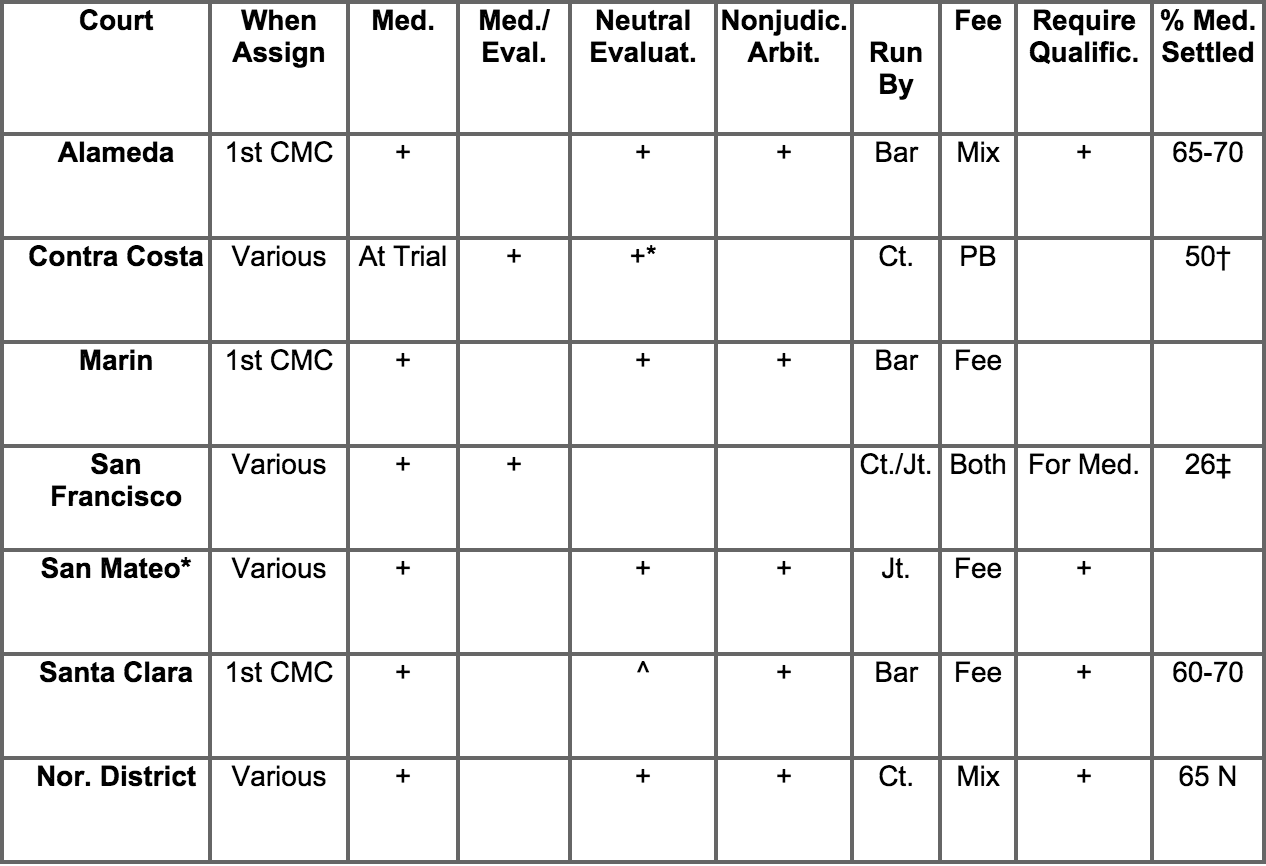

Chart of Local Court Procedures

The following is a summary of the local court-sponsored programs as well as some background about them. The information is not all inclusive and may not take into account all nuances of a program, so litigators should refer to local rules or speak with program directors for details. Some courts provide uncommon options not listed on the table; for example, the Northern District offers settlement conferences with magistrate judges and Santa Clara offers special masters. Most courts offer settlement conferences on the morning of trial, either with a judge or a judge pro tem, but only Contra Costa includes that in its ADR program.

The final column on the table below provides the percentages of cases which settle in the mediation program of the particular court. Some of these figures are based on statistics kept by the program managers and some are estimates. The box is left empty where there was too little data or the manager had no estimate.

Key:

* Pilot or trial program

CMC – case management or status conference

Various – Usually at judge’s suggestion at CMC , also on request of parties, or at filing

+ Provided

^ In development

Jt. – Joint court-bar program. In San Francisco, the Civil Mediation Program is run by the Court while ESP is joint.

Mix – part pro bono, part fee

PB – Pro bono under program, but some charge in EASE after 2 or more hours

Fee – Fee charged for all

Both – some programs PB, some fee

† For both EASE and SMART (at trial) programs

‡ Early Settlement Program; no figures available for newer Civil Mediation Program. ESP records show many other cases settle just before or just after the conference.

N All ADR programs combined

Confidentiality and Other Common Procedural Rules

There are certain procedural rules common to all the local programs. One of the most significant is the confidentiality of most ADR procedures, which is guaranteed by local rules and by statute. 3

California Evidence Code §1152.5 precludes the discovery or use of any admission or document made in the course of mediation. Section 1152.6 bars a mediator from submitting, and a court from considering, any report by a mediator other than a statement of agreement or nonagreement in the absence of the parties’ agreement. The passage of this statute in 1995 caused Contra Costa to change its reporting system in the EASE program. Formerly, the mediator described the parties’ settlement positions in some detail for the benefit of the Court during any later settlement discussions. Currently, the mediator provides such a report only with the parties’ unanimous consent, and otherwise states no more than that the mediation took place and whether the case settled.

Processes other than mediation are not specifically addressed in Section 1152.5, which on its face is limited to a mediation with “the purpose of compromising, settling, or resolving a dispute in whole or in part.” Evid. Code §1152.5(a). Local rules nevertheless assure the confidentiality of the EASE program and support the confidentiality of San Francisco’s ESP . 4

Some neutral evaluation procedures are also protected by rule or statute. In counties in which the ADR program is funded by the Dispute Resolution Programs Act (DRPA), locally Alameda and Santa Clara, that Act blankets all program procedures (including arbitration) with the protections of Section 1152.5. 5 Litigators should also be aware of Bus. & Prof. Code §467.4, which provides that agreements entered into in DRPA-funded programs are neither admissible nor enforceable in court unless the parties consent or explicitly and clearly state otherwise in the agreement itself. The pilot San Mateo program requires participants in a neutral evaluation to sign an agreement protecting all of the proceedings under Section 1152.5. 6 Other superior court rules do not address the issue. Most participants assume the proceedings and the evaluator’s opinion is confidential, but to be sure the parties should articulate that understanding in a written agreement.

In federal court, mediation and neutral evaluation are protected under ADR Local Rules 5-13 and 6-11, which extend the protections of Fed. R. Evid. 408 and Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 68 to these proceedings. There is no like protection in federal court for arbitration, either binding or non-binding. Arbitration testimony is taken under oath and subject to cross-examination. ADR Local Rule 4-1. 7

In non-DRPA counties, non-judicial non-binding arbitration is not protected absent an agreement of the parties. Presumably binding arbitration must be non-confidential, but in the DRPA-funded programs the parties should specify in a written agreement that they intend any result to be admissible and enforceable in court; absent such an agreement, it may not be. See Bus. & Prof. Code §467.4. In practice, arbitration decisions in Alameda County are not filed with the court and the process is treated as protected.

One of the main purposes of the confidentiality protections is to encourage the active participation of the clients in the process, because such involvement leads to more complete exchange of significant information and to more commitment to the process leading to an agreement. Meaningful participation requires the presence of the real decisionmakers: the party with authority, the insurance representative with authority, and the attorney who will try the case. Local programs share the requirement that these people must attend any session unless they obtain prior approval for nonattendance.

Finally, most courts will permit the parties to opt out of any court or bar program if they choose a private ADR provider. Where all sides agree on what they want, and pay for a private setting, the parties have more flexibility about selection of a provider and the timing and nature of the procedure.

Choosing the Right Procedure for Your Case

There is no way to create a comprehensive guide for deciding which procedure is best for a particular case. Often it is helpful to discuss this with program managers; the federal court program requires that the attorneys and the ADR Director or Program Counsel have such a discussion if the parties do not stipulate to a form of ADR on their own. The following is an outline of considerations.

Mediation is the choice in cases where immediate settlement is the goal. Mediation is also suitable where one side has information they wish to keep private, either about the case that is not yet disclosed or about the client’s circumstances which play heavily on settlement. A sophisticated litigator should consider what style of mediation is best for the case, whether more persuasive and facilitative or more evaluative and/or strong-arming. The litigator can then try to choose a mediator with the selected approach. In Santa Clara and San Mateo, mediators are asked to describe their style on forms available to attorneys making the choice.

Neutral evaluation is suitable where the parties are known to have widely different views of the case, although a “strong-arm” mediator can have the same effect. Neutral evaluation can also be especially useful in clarifying the issues of a case, defining a case management plan, and preparing a case for later settlement discussions when the parties are not yet ready. The focus of a neutral evaluation is on the presentation and exchange of information about the case, and so it often helps the parties to map out what discovery is most important. It is not an appropriate procedure if there is private information one party wishes to use without the other finding out. Neutral evaluation is not primarily designed to settle cases, although it often contributes to cases settling at the time or later.

Arbitration is suitable where a full presentation of a case is desired but without the expense of a trial. Parties more often select nonbinding arbitration because of concern about the finality of binding arbitration. Nonbinding arbitration may be appropriate for a simple case which can be adequately presented in a short time, or where a client is perceived as having a wholly unrealistic view of a case and/or as needing his or her “day in court” before a case can be resolved. It is also particularly appropriate where a cases turns on the credibility of witnesses. But nonbinding arbitration often does not resolve the case without further negotiation.

Selection of Providers, Qualifications and Fees

In court-endorsed programs in which providers may charge for their service, as for Alameda and Santa Clara mediations, the parties usually are given a short list of providers with backgrounds appropriate to the case from which to choose. In the voluntary San Francisco Civil Mediation Program, parties are provided a list of individuals and organizations of mediators who meet the Court’s eligibility requirements. In Marin, the parties are given the entire list of providers maintained by the bar which includes some background information. Some programs, such as the Contra Costa EASE and San Francisco ESP , assign providers to a particular case. The outgoing director in Contra Costa made it a practice to speak with counsel about a case to try to find the appropriate provider. In cases that are complex or have other special needs, counsel should discuss those circumstances with program directors to enlist their aid in finding the best possible provider, within the limits imposed by the rules of the programs.

Many programs permit providers to charge for their services, sometimes for reduced fees but often at market rates. 8 Mandatory programs and those strongly encouraged by the courts tend to be free or to include a substantial pro bono element. For example, in Alameda County providers agree to give without charge up to two hours of premeeting preparation time and two hours during the session. Litigants can usually “test the waters” of a mediation and judge whether it is worth continuing before being charged. In the Contra Costa EASE program, there is no provision for payment but providers can and do charge after donating some number of free hours (at least two and often more), but only after prior notice and with the agreement of all parties. In San Francisco, there is an administrative fee but no charge for the providers’ services in the Early Settlement Program, but providers in the more recently established Civil Mediation Program charge market rates. In federal court, there is no charge until after the first four hours of a mediation or neutral evaluation, and some providers do not charge at all.

Acknowledging the author’s obvious bias as an ADR service provider, litigators should not be overly concerned about the cost of these procedures. The expense is often negligible split between two or more parties, and is especially so compared to the savings to the parties that these procedures provide. The parties benefit not only when a case settles but also when they agree to a more streamlined procedure that leads to additional settlement negotiations, and when the lawyers get a better understanding of a case allowing them to focus on significant issues and to avoid unnecessary disputes.

Moreover, requiring parties to pay is often a major factor in making a procedure valuable. With the exception of binding arbitration, each of these procedures depends on the meaningful participation of all parties to maximize its benefit. Whether in mediation, neutral evaluation, or nonbinding arbitration, one side interested only in “free discovery” can put in no effort, with no intent to engage in realistic settlement discussions or to accept any outside evaluation, and try to benefit from listening to the opponent. Few if any sanctions can be imposed. Similarly, where a client is not actively involved but rather passively observes the attorneys sparring, a procedure is not as effective. When the client realizes that he or she is paying for the provider’s services, the client is more likely to participate and pay attention and the lawyers are less likely to treat the process lightly, increasing the chance for a tangible benefit.

Many providers are experienced, talented neutrals. Most court-sponsored programs demand certain qualifications of providers, which usually include three elements: years of experience as an attorney (at least 5 years, usually 7-10 minimum), 9 training in the particular procedure (for example, Alameda, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara require mediators to have completed a 40-hour course or comparable experience), and experience in providing the particular service (for example, five prior arbitrations or mediations). Although parties in some court-sponsored programs may not have the same range in choice of neutral available among privately-retained ADR providers, they may still get excellent service.

Conclusion

ADR is now an integral part of every lawsuit. Litigators need to plan how best to use ADR to benefit their clients, whether through a program sponsored by the court or privately. Understanding the options is the first step to intelligent decisionmaking.

List of Contacts

Alameda: Sally Rees, ADR Coordinator, County Bar, 510-893-7160 .

Contra Costa: Robin Siefkin, Director, ADR Programs, Superior Court, 510-646-2127 .

Marin: Steven Rosenberg, Chair, County Bar ADR Section, 415-383-5544 .

San Francisco: Connie Moore-Dunning, ADR Services, County Bar, 415-764-1600 ; Sue

Gershenson, ADR Program Director, Superior Court, 415-554-5883 .

San Mateo: Sheila Purcell, Multi-Option ADR Project, 415-363-4148 .

Santa Clara: Elizabeth Strickland, ADR Administrator, County Bar, 408-287-2557 .

U.S. District Court: Mimi Arfin, ADR Program Director, 415-522-2022 ; Howard Herman, ADR Program Counsel, 415-522-2027 ; Carroll DeAndreis, ADR Program Administrator, 415-522-2199 .

© 1997, David J. Meadows

1 ADR is an acronym for both alternative dispute resolution and appropriate dispute resolution. This article addresses the court-sponsored ADR programs for general civil litigation, not special programs such as family law mediation, attorney fee dispute arbitration, and community dispute mediation. Information about these programs may be obtained from the contact list provided at the end of the article.

2 There is no statutory authority for superior courts to order parties to mediation, Kirschenman v. Superior Court, 30 Cal. App. 4th 832, 835, 36 Cal. Rptr. 2d 166 (1994), except in Los Angeles and in other courts electing to apply the pilot project for Civil Action Mediation, Code Civ. Pro. §§ 1775 et seq., which provides that cases can be ordered into mediation where the amount in controversy does not exceed $50,000. Id. §1775.5.

Consistent with the state policy announced in the California Dispute Resolution Programs Act, Bus. & Prof. Code §§ 465 et seq., all local superior courts have policies to raise ADR at the first case management or status conference and to encourage the parties to pursue it. See Alameda Local Rule 4.0(3)(a), 4.3 & 4.4(2)(g); Contra Costa Local Rule 5(e)(8) & 5(I), Appendix C, §§ 101, 102; Marin Local Rule 5.05, 5.09 & 5.09.1; San Francisco Local Rule 2.4(4)(G), 2.5(4)(3), 2.13 (Early Settlement Program, treated as part of the Court’s settlement calendar and therefore can be mandatory), & 18 (voluntary Civil Mediation Program, added in 1995); San Mateo Local Rule 2.3(a)(3), (e)(5)(A) & (F); Santa Clara Local Rule 1.1.6(D)(3)(b).

3 Changes to these statutes are currently being considered by the California legislature.

4 Contra Costa local rules describe EASE sessions as mediations subject to Evid. Code §§ 1152.5 and 1152.6. Local Rules, App. C §207. San Francisco rules describe ESP as a quasi-judicial proceeding akin to a settlement conference conducted by a judge, see S.F. Local Rule 2.13(A), (C) & (K), and presumably subject to the same confidentiality protections, although at present there are no explicit rules to that effect.

5 Bus. & Prof. Code §467.5: “Notwithstanding the express application of Section 1152.5 of the Evidence Code to mediations, all proceedings conducted by a program funded pursuant to [the DRPA] including, but not limited to, arbitrations and conciliations, are subject to Section 1152.5 … .”

6 San Mateo Multi-Option ADR Project Neutral Evaluation Guideline 11.

7 If either party requests a trial de novo, the arbitration award is sealed and cannot be disclosed to an assigned judge until the action is terminated. ADR LR 4-12(c).

8 In many of the programs in which providers can charge, the providers agree to handle some cases pro bono where the parties lack the means to pay, and other cases at reduced rates for those of modest means. This is true in Alameda, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara.

9 Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo permit non-attorney neutrals with comparable experience.