The use of mediation and other Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) procedures has continued to grow over the past several years, both privately and through the court-sponsored programs that have flourished in the Bay Area. Meanwhile, the scope of the confidentiality blanketing mediation is becoming clearer, and more limited, as case law addresses new and difficult issues. This article provides a brief update on these developments.1

Local Court ADR

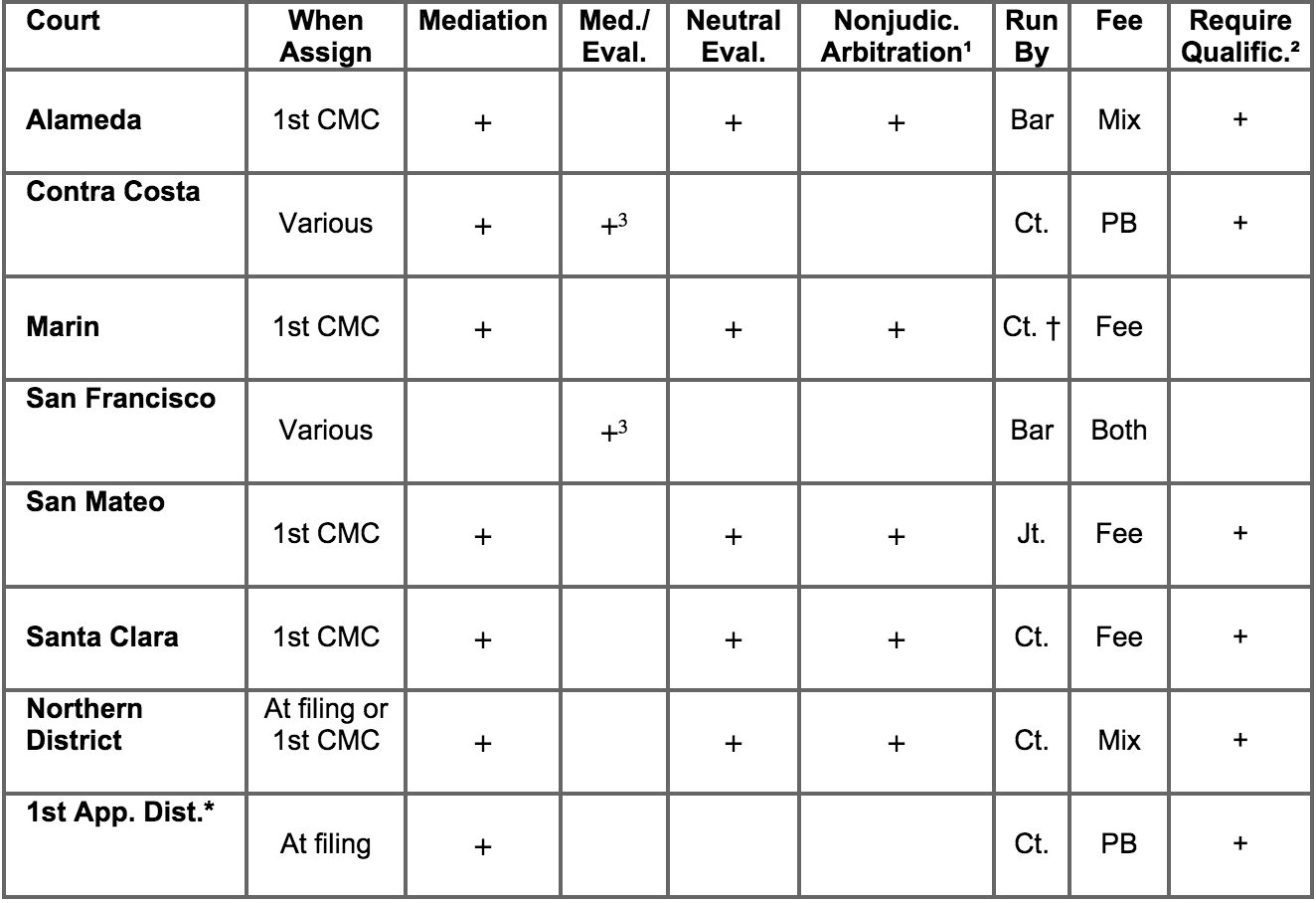

The chart below summarizes the existing local court-sponsored ADR programs. The information is not all-inclusive, so practitioners should check local rules or contact the program directors listed below for more details.

Key & Notes:

1. Judicial arbitrations are provided through the superior courts, although many litigators are now choosing mediation rather than mandatory arbitration where possible pursuant to C.C.P. §1775.3(a) or local rule.

2. Qualifications may be required for neutrals, usually including both training and experience with the particular procedure.

3. The Contra Costa EASE program (Extra Assistance to Settle Early) and the San Francisco ESP (Early Settlement Program) are hybrid procedures intended to involve both evaluation and mediation techniques; in practice they are usually conducted as evaluative-style mediations.

* New program beginning in 2000

CMC – case management or status conference

Various – Assignment to ADR usually at judge’s suggestion at CMC ; can also be on request of parties

+ Provided

Jt. – Joint court-bar program. In San

Francisco, the Civil Mediation Panel is run by the Bar while ESP is joint.

Mix – part pro bono, part fee

PB – Two hours pro bono under EASE program, but most providers charge thereafter; six hours pro bono in 1 st App. Dist. No charge for preparation in either.

Fee – Fee charged for all; usually PB available for low-income

Both – some programs PB, some fee

† – In Marin, the Court maintains binders of providers’ names that are compiled by the Marin Bar Association ADR Section.

It has now become almost universally institutionalized that at the first Case Management Conference the Court will require counsel at least to consider ADR. Generally, California courts make ADR voluntary.2 Consistent with the state policy announced in the California Dispute Resolution Programs Act, Bus. & Prof. Code §§ 465 et seq., all local superior courts have policies to raise ADR at the first case management or status conference and to encourage the parties to pursue it. See Alameda Local Rule 4.0(2)(a), 4.3(1)(A) & 4.4(2)(g); Contra Costa Local Rule 5(d)(8) & 5(i)(4)(a)(2), Appendix C, §§ 101, 102; Marin Local Rule 1.25(C)(2); San Francisco Local Rule 3.4(F), 4.0, 4.2, & 4.3 (Early Settlement Program can be mandatory, presumably because treated as part of the Court’s mandatory settlement calendar); San Mateo Local Rule 2.3(a)(3), 2.3(e)(5)(A) & (F), 2.3(h); Santa Clara Local Rule 1.1.6(D)(3)(b). Anecdotally, a number of attorneys have informed me that some judges will strongly encourage mediation to the point that counsel are in effect compelled to attempt mediation or some form of ADR. In federal court, the new Proposed Local Rules mandate that all cases be assigned at filing to the Multi-Option ADR Program or to non-binding arbitration.3 All eligible cases, essentially contract and tort cases seeking less than $150,000 in damages, are presumptively assigned to arbitration subject to the parties opting out if they prefer mediation or another ADR process. Counsel in all other cases must select an ADR process or the Court will choose one for them.

There is one entirely new program beginning this year. The First Appellate District has hired John Toker, formerly ADR director in the Santa Clara Superior Court, to administer its pilot mediation project. Toker assigns some cases mandatorily into mediation, while in other cases the parties can request assignment as well. Several mediations have already been initiated.

Contra Costa County also is beginning a new option within its ADR processes. It has received Judicial Council funding to administer the experimental Early Mediation Program, to which cases are voluntarily assigned at the first Case Management Conference.4 Meanwhile, over the past two years the number of cases managed by the Contra Costa EASE program has almost tripled, from about 35 cases per month to about 84 per month.

Other programs have experienced similar growth. The San Mateo Multi-Option ADR Project, for example, had just opened its doors two years ago and now is handling 30-50 cases per month.

In some programs, there have been extensive changes in personnel recently. The Alameda County Bar Association ADR Placement Service, which works closely with the Court, is now on its fourth director in two years, Diana Compton. In San Francisco Superior Court, the position of ADR Program Director has been vacant for more than a year. It appears that the Court is willing to let BASF carry the bulk of the Court’s ADR practice through the Early Settlement Program (a puzzling name as cases are usually assigned approximately two months before trial), and to leave the parties to their own resources otherwise. By contrast, in Santa Clara County the Court took its ADR program in-house, making the County Bar Association service obsolete, although the Superior Court’s new ADR administrator is Elizabeth Strickland, who had been running the Bar program.

Contact numbers for all these programs follow:

Court Contact Person/Organization Phone

Alameda Diana Compton, Alameda Bar ADR 510-893-7160

Contra Costa Robin Siefkin, Court ADR 925-646-2127

Marin Irene Mariani, Court Clerk 415-499-6072

San Francisco Connie Moore-Dunning, SF Bar ADR 415-982-1600

San Mateo Sheila Purcell, Multi-Option ADR Project 650-363-4148

Santa Clara Elizabeth Strickland, Court ADR 408-299-3090

Northern District Mimi Arfin, ADR Director 415-522-2022

Howard Herman, ADR Counsel 415-522-2027

Carol DeAndreis, ADR Administrator 415-522-2199

1st App. Dist. John Toker, Court ADR 415-865-7375

Mediation: How Confidential Is It?

California practitioners have come to regard the confidentiality provisions of Evidence Code §§1115 et seq., in particular Section 1119, as affording virtually absolute protection against post-mediation disclosure.5 A recent case and the most recent draft of the Uniform Mediation Act create a doubt about the extent to which this will remain true.

In Olam v. Congress Mortgage Company,6 Magistrate Judge Brazil held that, notwithstanding the provisions of Section 1119, a mediator can be compelled to testify about the statements and conduct occurring at a court-sponsored mediation where (1) one party challenged the enforceability of a written settlement agreement entered into at the mediation, (2) both parties stipulated to disclosure of otherwise confidential information from the mediation, and (3) the Court held an in camera hearing to determine the materiality of the mediator’s testimony before making it public. The issue arose after a party sought to defeat a motion to enforce the agreement by claiming she signed only as a result of undue influence.

This is the first time in California a mediator has been compelled so to testify in a fairly typical civil case. It is probably not an aberration, however. Magistrate Judge Brazil is respected for his knowledge of ADR and strong participation in the direction of the Northern District’s ADR Program as the designated ADR Magistrate Judge. Analytically and procedurally, he closely followed a 1998 California Court of Appeal decision, Rinaker v. Superior Court.7

In Rinaker, the Court of Appeal required a mediator to testify over the objection of one of the parties and the mediator in a juvenile delinquency hearing, nominally a civil proceeding and therefore subject to Section 1119. The court’s rationale was that the minor’s constitutional due process rights to confront and cross-examine the witnesses against him trumped the mandates of mediation confidentiality. These constitutional rights required that the juvenile be permitted to impeach a witness with the witness’s conflicting statements made at the mediation, notwithstanding the statutory promise of confidentiality and the values supporting it. Rinaker’s holding clearly derives from the quasi-criminal character of the proceeding where a juvenile faces confinement or other sanctions.8

A key difference between Rinaker and Olam arises from the values impacted because of the setting. While Rinaker raised an issue over a minor’s right to cross-examine witnesses where his freedom was at stake, Olam concerned a private party’s efforts to avoid an agreement she had signed. Nonetheless, the Olam decision is generally consistent with the draft Uniform Mediation Act (“UMA”),9 and a number of court decisions and statutes in other states. Under the UMA, disclosure of confidential communications is permitted in a variety of circumstances not specifically delineated in Section 1119. Of special note is Section 8(b)(2), which would permit disclosure of mediation communications in “a proceeding in which fraud, duress, or incapacity are raised regarding the validity or enforceability of an agreement.” The Reporter’s Notes from an earlier draft make it clear that this is intended to preserve all contract defenses “which would otherwise be unavailable if based on mediation communications.”

While the UMA directs that its provisions should be construed to protect confidentiality “subject only to overwhelming need for disclosure to accommodate specific societal purposes,”10 this is not a bright line test.

The scope of the exception opened by Olam remains unclear. California state courts may not follow the decision.11 By its own terms it is limited to the rather unusual circumstance that both parties waived any claims they had to confidentiality.12 While a mediator in California also has the right to assert confidentiality,13 the Olam court clearly considered the parties’ joint choice to waive their rights as substantially reducing society’s and the mediator’s interests in maintaining the confidentiality of this mediation. Slip. Op. at 35-36.

But the context of Olam is particularly troubling. One of the parties changed her mind about the agreement that she signed, and claimed that she was coerced into signing it, did not understand it, and should be permitted to avoid it because it was obtained by undue influence. Analytically, it is difficult to distinguish this case from any other situation where one of the parties wishes to avoid a settlement agreement on the basis of any defense to a contract, such as fraud and misrepresentation, economic duress, undue influence, etc. All of the arguments raised by the Olam court and by the UMA Reporters, concerning the necessity of disclosing confidential communications in order to consider such defenses fully and fairly, apply with equal force in virtually every case in which a party seeks to avoid a written settlement agreement. In other words, just when it looks like the parties have achieved finality by making an agreement in a mediation, a party seeking to avoid that agreement can threaten to disclose in a court proceeding all the confidential communications from the other side, made directly or through the mediator.

I am persuaded that this is bad for mediation in California , notwithstanding the probable rarity of disclosure in this context. Uncertainty over confidentiality is likely to constrain some participants from disclosing particularly sensitive information to the other side for fear that they will be “held up” by their opponent’s later threats to challenge enforceability and make the sensitive information public. Courts can protect against this by not permitting disclosure unless all parties agree and by holding in camera hearings, as in Olam and Rinaker and as directed by the UMA, to screen unnecessary and inappropriate material from being publicly disclosed. But any assurance that this will happen must await further case law.

Even aside from the concern for confidentiality, the Olam rule encourages arcane and unnecessary court proceedings. The parties may have to litigate what assertions constitute fraud, what factual basis supported various statements made in the mediation, whether negotiating postures (statements such as “I’ve been directed to accept no less than/pay no more than $___”) are actionable, and the like. It is an exception that may be severely counter-productive to mediating agreement in some cases.

Moreover, all the same concerns can be protected against in other ways. If parties wish to reserve the right to challenge the validity of an agreement if a specific factual representation later proves false, they can rely on traditional contractual devices, such as warranties made in the written agreement. Demanding such warranties would be effective for determining whether a party can rely on the information, and would not require disclosure of otherwise confidential information. In this way, the value of encouraging open communication at a mediation and the interest in protecting against another’s material misrepresentations are both supported. Other defenses, such as duress or undue influence, should only be available where a party is not represented; where parties are represented the claim should be available only as a claim against the attorney. A party’s autonomy is thus protected without sacrificing the general rule of confidentiality.

But for now, participants in mediation should be aware of the risks of disclosure if an agreement is reached. Parties and counsel are advised to consider protecting themselves by entering a confidentiality agreement that goes beyond the language to Section 1119 where circumstances warrant it.

*David J. Meadows provides mediation, arbitration, and other ADR services from his Oakland office both privately and through a number of court-annexed programs. He has conducted hundreds of ADR proceedings, the majority mediations, and is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Law at Hastings College of Law teaching Alternative Dispute Resolution.

1 The author wrote a longer article on local court ADR programs two years ago: Meadows, Charting a Course Toward Dispute Resolution: A Summary of Bay Area Court ADR Programs, San Francisco Attorney (December 1997).

2 There is no broad statutory authority for superior courts to order parties to mediation, Kirschenman v. Superior Court, 30 Cal. App. 4th 832, 835, 36 Cal. Rptr. 2d 166, 168 (1994)[but see Lu v. Superior Court, 55 Cal. App. 4 th 1264, 1270-71, 64 Cal. Rptr. 2d 561, 565-66 (1997)(court can order parties to private mediation under inherent authority of Code Civ. Pro. §187 in complex case where mediation designated as mandatory settlement conference)], except in Los Angeles and in other courts electing to apply the Civil Action Mediation Act of 1993, Code Civ. Pro. §§ 1775 et seq. (which provides that cases can be ordered into mediation where the amount in controversy does not exceed $50,000, id. §1775.5), or the new pilot Early Mediation Program, Code Civ. Pro. §§1730 et seq. (which authorizes funding for two counties to run a mandatory mediation program and two courts to run a voluntary version, id. §1730(a); Fresno and San Diego will run mandatory programs, while Contra Costa and Sonoma will run voluntary ones). In addition, pursuant to a new local rule the pilot mediation program of the First Appellate District will be mandatory in selected cases.

3 Proposed Local ADR Rule 2-3(a). This was in response to the direction of the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 1998, 28 U.S.C. §§651-58, for district courts to authorize by local rule the use of at least one ADR process in all civil actions. The Proposed Local Rules will be implemented in April if they receive final approval.

4 This program is part of the state-funded pilot Early Mediation Program, Code Civ. Pro. §§1730 et seq. See note 3 supra.

5 “No evidence of anything said or any admission made … in the course of, or pursuant to, a mediation … is admissible or subject to discovery, and disclosure of the evidence shall not be compelled, in any … noncriminal proceeding … .” Evid. Code §1119(a). See also Evid. Code §703.5 (mediator shall not be “competent to testify” in any subsequent civil proceeding about any statement or conduct occurring at the mediation, unless the statement or conduct constitutes a crime, is the subject of a State Bar investigation, or — presumably only when the “mediator” is a judge — gives rise to civil or criminal contempt, is the subject of an investigation by the Commission of Judicial Performance, or gives rise to disqualification proceedings under Code Civ. Pro. §170.1).

6 Amended opinion, 1999 WL 909731, N.D. Cal. No. C95-2608 (October, 1999).

7 62 Cal. App. 4th 155, 74 Cal. Rptr. 2d 464 (1998).

8 62 Cal. App. 4th at 165; 74 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 469.

9 I refer herein to the draft as revised during the January 28-29, 2000 meetings. The UMA will remain a draft subject to continual change at least through its final reading in July, 2000. Drafts and Reporters’ Notes can be accessed through the official website (author’s note: updated information 2005) www.law.upenn.edu/bll/mediate/UMA2001.htm. More recent drafts can sometimes be found through www.ronkelly.com. The numbering used herein is based on the “rough draft” including the latest changes found at the latter site. The “rough draft” is unclear at times but most terms quoted herein are carried over from earlier drafts, although often with a different section number.

10 Section 4(c). The recent federal Administrative Dispute Resolution Act of 1996, 5 U.S.C. §§571-584, has a similar provision, permitting disclosure “to prevent manifest injustice.” Id. §574(a)(4)(A). The commentary to the Proposed Local ADR Rules of the Northern District provide some examples of extreme cases where courts have permitted disclosure of otherwise confidential communications, in addition to Olam: “threats of death or substantial bodily injury (see Or. Rev. Stat. Section 36.220(6)); use of mediation to commit a felony (see Colo. Rev. Stat. Section 13-22-307); right to effective cross examination in a quasi-criminal proceeding (see Rinaker v. Superior Court, 62 Cal.App.4th 155 (3rd Dist. 1998)); lawyer duty to report misconduct (see In re Waller, 573 A.2d 780 (D.C. App. 1990)); need to prevent manifest injustice (see Ohio Rev. Code Section 2317.023(c)(4)).”

11 The opinion is written by a federal magistrate judge and is not binding on state courts. Strikingly, most of its analysis was unnecessary to the decision in the case because the Court acknowledged that the testimony of the party challenging the agreement, even if fully believed, was not sufficient to support a finding of undue influence. Slip op. at 62. Thus, the Court could have reached the same result without requiring the mediator’s testimony.

12 Agreement of all parties would not be required under the UMA where fraud, duress, or incapacity are raised to invalidate an agreement entered into through mediation, at least for evidence from the parties and counsel; ironically in light of Olam, the current draft of the UMA would not permit testimony from the mediator. Section 8(b)(2)

13 Under Evid. Code §1122, a waiver of confidentiality is only valid if all participants, including not only the parties but the mediator and any other nonparties, agree. See Law Revision Commission Comments – 1997 Addition. The UMA provides that the mediator has some limited confidentiality rights independent of the parties, although only with regard to the mediator’s own mediation communications. Section 2(b).